Blog

Postings arise as time permits

and inspiration hits. Contact me

to request a special topic!

and inspiration hits. Contact me

to request a special topic!

|

Do you remember the first time you thought your instrument was awesome? I was a freshman at the University of Georgia, and a doctoral student performed Andre Previn's Sonata for Bassoon and Piano, and I am pretty sure my mouth actually dropped open. I was so nerdishly giggly and head over heels in love. I swore that I would play it "when I was ready" (whatever that meant to 18-year-old Cayla). I didn't even listen to it again for a long time, purely out of fear that in the harsh light of a second listening I would fall out of love. I did in fact play it later (see a clip from my first doctoral recital here) and will again this coming spring. It has not been until years later, though, that I realize what actually happened in that moment. I thought the bassoon and its music were awesome. After that performance, I started hearing the potential for awesome in everything. There was a good bit in Saint-Saens, there was some in Mozart, there was a lot in Vivaldi, and most recently there was way more than I expected in Gubaidulina. From that point on, everything new could potentially be knock-me-to-the-floor awesome. So I'll ask again: do you remember the first time you thought your instrument was awesome? In addition to being a warm fuzzy and self-assuring sentiment, this realization has motivated me through the tough practice sessions lately. While I've written before about the tools of slow and the dangers of angry practicing, this is even more fundamental. For me, this has been the answer to the "why am I doing this?" These past few weeks, I have been working on David Maslanka's Sonata. In a break from one particularly tricky section, I wandered my way onto Instagram: Pouring in the blood, sweat, and tears for the potential of awesome is one thing. For years, that has been enough. Now I realize that I work not only to realize the potential of awesome in a performance, but also to potentially create a moment where someone first realizes that the bassoon and its music are awesome. That music as a whole is pretty awesome.

What if you were the moment someone realized music is awesome? Now get to it. Go be awesome.

3 Comments

Okay, I get it. Slow down. In my experience, this is by far the most frequent practice advice given. In their exceedingly popular music blogs, Noa Kageyama asks "Is Slow Practice Really Necessary?", Gerald Klickstein explores "A Different Kind of Slow Practice", and Daniel Coyle shows us all how "Slow is Beautiful." Okay, I get it. For determined practicers, the problem is often not that we don't practice slowly. The problem is that we don't know how slowly. We show up to lessons insisting that we have been practicing slowly (usually we're not lying), and we hear week after week to practice slower. But slow is boring, and slow is confusing. How slow is slow enough? THE LONG(ER) ANSWER: I turned to the idea of mindfulness. Most basically, mindful practicing meant being aware of everything, all the time. When I did that, I practiced slowly and deliberately enough to see relaxed, lasting change. Without going too far into the psychology and meditation side of the movement, I found an ideal practice tempo by tapping into multiple senses. Specific questions helped:

Focusing on real-time sensations rather than long term goals slowed me down. I practiced less angrily. Repetitions felt like experiences, not like plateaus. The absolute best part about it, though, was that everything sounded like I wanted it to sound. I was like a kid in the nerdiest candy shop ever. Now for THE SHORT(EST) ANSWER: No: Practice so you can do everything right. Yes: Practice so you can do nothing wrong. Happy (slow enough) practicing!

"Hey, will you come listen to something?" At some point, we have all asked for feedback. Sometimes we ask explicitly, dragging people from the halls into our practice room to hear an excerpt, and sometimes it is the implicit request we make every time we show up for a lesson. This post is purely about that - asking for feedback. A couple of weeks ago, I read this article in the Chronicle for Higher Education. It is not about music, but many of the points resonated in my immediately-pre-audition mind. When we ask someone to critique our playing, what do we really want? In case you didn't actually read the article, I'll summarize - Allison points out that we need to be specific in what we want from our listeners. To translate her categories to music, we can ask for one of five types of feedback:

If you do indeed want feedback - you have asked for categories 1, 2, or 3 - the next step is interpreting what you receive. At this point in my thinking, I returned to the array of internet wisdom and found this post. The important part is what this suggests about interpreting feedback. Despite the catastrophic mentality of some of us, all critiques are not this: Similarly, if your critic says anything at all, it does not mean this: I venture to say that 99.a lot% of feedback lies somewhere between levels 1 and 9, and how we as players choose to respond to that feedback influences our future progress. To translate the author's example to music and add an extra interpretation of my own:

Feedback - "Your double-tonguing in Marriage of Figaro is too short." Interpretations -

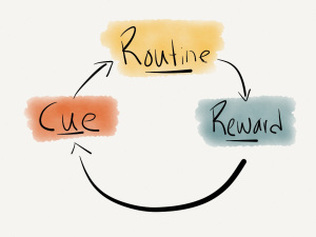

Again, perhaps the most helpful interpretation of feedback lies somewhere between the extremes. As someone who tends toward the unclear feedback requests and catastrophic level 10 interpretations, I am making it my personal mission to shift my perspective. So here it is - if you see me practicing at any point this spring, come on in and listen. I'll be specific and do my best not to enrage the beast. "Practice doesn't make perfect. Practice makes permanent." Sound familiar? This idea of habit formation has been central to my most recent "Lap Four" goal - see my earlier post if you're confused. Historically, I have problems with consistency. One day I play a brilliant concerto, the next I forget how to slur an octave. Home run, strike out. In my multifaceted approach to solve this problem (and subsequent random internet surfing), I came across several videos, web resources, and a book by New York Times writer Charles Duhigg. He describes the "Habit Loop," which led me to two important realizations:

I set out to deconstruct my habit loop. CUE: Public performance. ROUTINE: Freak out, lose control. REWARD: An "engaging" performance. Sometimes this is a euphemism, sometimes not. Here's his story, the cookie-based version of my bassoon habit: After months of diligent work refocusing on the reward - engaging an audience with a musical experience - I finally stepped beyond my most recent plateau. I played in a master class, and, for the first time in what felt like forever, I was happy with what I presented.

I played representatively. I played how I play when I'm alone. I played how I play when I am having fun. *gasp* A friend of mine asked me later that evening what I felt to be the biggest change in my playing over the past several months, and I gave him a highly inadequate answer. (So, this post is partially for you, Adam!) I gave him a technical answer. I did blah blah to my reeds and think of my sound as blah blah and by body blah. Blah. After more reflection, here's the real answer: I practiced right. By "right" I don't mean that I was practicing wrong before. I mean I practiced being right and knowing I could be right. I practiced being right more than I was being wrong, which I had always before thought of as a waste of time. However, it stands to reason that we will always do what we have always done. If nine times out of ten you crack a note, that one success only means that you have a 10% chance the next time around. Play it correctly ten times in a row, then your chances just over 50% (11 rights for 9 wrongs). Math! I stopped practicing to be perfect, and I started practicing to be permanent. I practiced right, and it felt right. Go give it a shot, and let me know what you think! Warning: This post contains moments of tough love. Why do you practice? To move up in your section? To reach higher than your personal best? To increase your ability to connect with an audience? Up means improvement and success. Just take a look at my Google image search for "success": In practicing and learning, those "up" moments are brilliant. They encourage us, console us, validate us. Sure, the "down" moments sting, but it's the prolonged periods of parallel motion that are truly devastating. It hurts to work and feel no progress, it hurts when dedication doesn't seem to matter, and it hurts to watch others improve while you're stuck on cruise control. Plateaus are the worst. So now I offer you three "UP"s as options to take until you reach your next "up".

To conclude: I had a teacher once who equated the process of practicing and improving over the long-term to climbing a mountain - it is only at the end of your climb that you realize how high you've reached. In the meantime, though, remind yourself what you can do. Tell yourself you're awesome, because you are to someone (even if not yourself). Some plateaus can be just plain beautiful. Early in the process of learning new music, I generally experience the following stages:  1. Sheer excitement - characterized by wild sight-reading with little to no regard for mistakes  2. Childlike optimism - characterized by a bizarre joy for drilling technique and fundamentals, accompanied by frequent positive visualizations of future performances  3. Reality strike - characterized by the identification of true trouble passages, occasionally leading to angry practice This concept of angry practice is something I have been focusing on in my latest adventure into new repertoire study, and today was my first instance of its ugly head rearing in a practice session. I chose the image of super-angry "El Toro" above in part because he is, indeed, super-angry, but also in part because angry practice became a clear tendency of mine on the baseball (softball) diamond. To this day, my dad will reference the softball version of angry-practicer Cayla whenever I describe coming up against failure. I spent a good deal of my youth softball days as a pitcher, and I would feel the anger boil almost every time I just couldn't get the sinker to sink or the change-up to change up. Or the strike to be a strike. I would stand on the mound and set my jaw (my muscles clench a little just thinking about it). I would breathe like a bull about to skewer a toreador, and I would snap the ball in my glove. Snap, snap, snap. That's what we do as musicians in the same situation. Cracking the articulated A every time? MASH THAT VENT KEY! Uneven sixteenth notes? TAP YOUR FOOT REALLY HARD! AND SLAM YOUR FINGERS! Under-supported interval slurs? PLAY THEM REALLY LOUDLY! Unsurprisingly, these overly-physical, emotionally-driven are not always conducive to good learning. More often than not, the extra drive (my polite way of saying blind anger) drives up the tempo and dynamic of our practice sessions, making it even less likely that we succeed. Contrary to the advice you may expect, however, I am not about to tell you to calm down. Firstly, rarely are emotional states truly in our control. Secondly, being angry means that you care, and that is wonderful. Thirdly, emotion drives our expression far more than flawless technique. This guy may have some expressive issues - - but, you know what, so does this guy: So what do you do?

Angry practice is not good, but anger is not bad. Rather than rattle off a string of unsupported advice, I would rather simply reflect on how I am currently dealing with this trend in my own practice. For me, the answer to this contradiction lies in the fact that the anger is energy, and we all need energy in some facet of our playing. Focus the fundamental raw energy of the anger on the things in your own personal playing that need an extra kick - for some that is grounded connection with the chair or floor, for others it is embouchure engagement. For us all it is probably airspeed and motion through the phrase or between note changes. I tried this today in one particularly troublesome measure of Bozza's Recit, Sicilienne, and Rondo that I am planning to perform in July. After spending the standard five minutes letting my angry energy reveal itself in the blunt force trauma to my fingertips as I wildly slapped at an E to F-sharp connection, I stepped back (literally, took a little walk) and contemplated where I could better use that energy. In this case, I needed a more successful voicing, and I was pleasantly surprised at the change in atmosphere of my practice session after. Success! My angry practicing had become energetic focus. Now... on to the task of replicating this experience. What ways have you found to redirect or defuse angry practicing? Really, I'm curious. Comment away! |

Archives

October 2020

Categories

All

|