Blog

Postings arise as time permits

and inspiration hits. Contact me

to request a special topic!

and inspiration hits. Contact me

to request a special topic!

|

Do you remember the first time you thought your instrument was awesome? I was a freshman at the University of Georgia, and a doctoral student performed Andre Previn's Sonata for Bassoon and Piano, and I am pretty sure my mouth actually dropped open. I was so nerdishly giggly and head over heels in love. I swore that I would play it "when I was ready" (whatever that meant to 18-year-old Cayla). I didn't even listen to it again for a long time, purely out of fear that in the harsh light of a second listening I would fall out of love. I did in fact play it later (see a clip from my first doctoral recital here) and will again this coming spring. It has not been until years later, though, that I realize what actually happened in that moment. I thought the bassoon and its music were awesome. After that performance, I started hearing the potential for awesome in everything. There was a good bit in Saint-Saens, there was some in Mozart, there was a lot in Vivaldi, and most recently there was way more than I expected in Gubaidulina. From that point on, everything new could potentially be knock-me-to-the-floor awesome. So I'll ask again: do you remember the first time you thought your instrument was awesome? In addition to being a warm fuzzy and self-assuring sentiment, this realization has motivated me through the tough practice sessions lately. While I've written before about the tools of slow and the dangers of angry practicing, this is even more fundamental. For me, this has been the answer to the "why am I doing this?" These past few weeks, I have been working on David Maslanka's Sonata. In a break from one particularly tricky section, I wandered my way onto Instagram: Pouring in the blood, sweat, and tears for the potential of awesome is one thing. For years, that has been enough. Now I realize that I work not only to realize the potential of awesome in a performance, but also to potentially create a moment where someone first realizes that the bassoon and its music are awesome. That music as a whole is pretty awesome.

What if you were the moment someone realized music is awesome? Now get to it. Go be awesome.

3 Comments

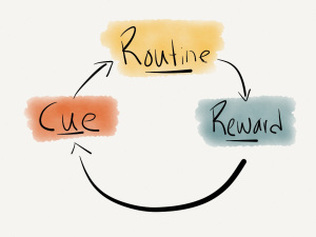

"Practice doesn't make perfect. Practice makes permanent." Sound familiar? This idea of habit formation has been central to my most recent "Lap Four" goal - see my earlier post if you're confused. Historically, I have problems with consistency. One day I play a brilliant concerto, the next I forget how to slur an octave. Home run, strike out. In my multifaceted approach to solve this problem (and subsequent random internet surfing), I came across several videos, web resources, and a book by New York Times writer Charles Duhigg. He describes the "Habit Loop," which led me to two important realizations:

I set out to deconstruct my habit loop. CUE: Public performance. ROUTINE: Freak out, lose control. REWARD: An "engaging" performance. Sometimes this is a euphemism, sometimes not. Here's his story, the cookie-based version of my bassoon habit: After months of diligent work refocusing on the reward - engaging an audience with a musical experience - I finally stepped beyond my most recent plateau. I played in a master class, and, for the first time in what felt like forever, I was happy with what I presented.

I played representatively. I played how I play when I'm alone. I played how I play when I am having fun. *gasp* A friend of mine asked me later that evening what I felt to be the biggest change in my playing over the past several months, and I gave him a highly inadequate answer. (So, this post is partially for you, Adam!) I gave him a technical answer. I did blah blah to my reeds and think of my sound as blah blah and by body blah. Blah. After more reflection, here's the real answer: I practiced right. By "right" I don't mean that I was practicing wrong before. I mean I practiced being right and knowing I could be right. I practiced being right more than I was being wrong, which I had always before thought of as a waste of time. However, it stands to reason that we will always do what we have always done. If nine times out of ten you crack a note, that one success only means that you have a 10% chance the next time around. Play it correctly ten times in a row, then your chances just over 50% (11 rights for 9 wrongs). Math! I stopped practicing to be perfect, and I started practicing to be permanent. I practiced right, and it felt right. Go give it a shot, and let me know what you think! Summer. If you're a student, this tends to be the time of goal-setting and returning to fundamentals. (Stay tuned for a burnout post, coming shortly.) As I finish up another academic year, I find myself entering summer with just that approach. Get in the practice room! Play scales! Make reeds! After all, these are the building blocks... aren't they? Why, then, do we feel so frustrated with the inevitable plateaus of learning? We have been taught for years that relevant short-term goals and focused work will lead to our long-term goals. Diligent major scales and long tones win auditions. I was (relatively) happily sweating away at the gym last week when the great flaw of this was literally right in front of my face. With the elliptical machine as my weapon of choice, this spring I set a semester goal of going from total gym avoidance to breaking five miles in 45 minutes, and I had been clocking in around 47 minutes for weeks. I had also been doing what I had been trained to do with long-term goals, trusting the fundamentals - focusing on breathing, smooth body motion, even pacing. For weeks I would enter the last mile and a half with an extra burst of energy, and for weeks I would fail. I don't know what inspired me on Wednesday, but I decided to start focusing earlier than the last mile and a half. What if I started paying attention to the middle step? Specifically, I wanted to hit three miles at 27 minutes and four at 36. Unsurprisingly, it worked. With almost no extra physical effort, I shaved a solid three minutes off my average five mile time simply by gearing my efforts to the "middle-term" goals. This got me thinking. What if I can do so much more in music than I think, simply by shifting focus? What if I can play a magical Mozart Concerto if I just bother to set my sights on something in the abyss between a B-flat major scale and a moving, stylized, engaging performance? Essentially, I realized I needed this guy: Remember him? He's the guy in Mario Kart who picked you up when you drove off the road. He also measured your mid-race progress. Lap four at just under 38 seconds. Not getting the turbo boost to lead off in first (B-flat major scale) or standing on the top of the podium at the end (from your Mozart Concerto, of course).

What is your "lap four" goal? Really, though, leave it in the comments field below. This is the goal that falls by the wayside. We do the work of the short-term goals with our eyes on the long and forget to have a means to measure the gulf in between. Most times it is very clear how to set a short-term goal for a week - what was I assigned in my lesson? It is also very clear how to set a long-term goal for a year - what is on my recital/jury/audition? The middle steps are much more elusive, though. What do you personally want to see, hear, and feel in yourself as a musician in a month? What about two or three? Can you make these specific, independent goals and state them without referencing your short- or long-term goals? By this, I mean that a "lap four" goal is not just to play your scales more in tune or your concerto under tempo. It's trickier than it sounds to set this kind of milestone, and I will leave you with that charge. Ready? Set. ... |

Archives

October 2020

Categories

All

|