Blog

Postings arise as time permits

and inspiration hits. Contact me

to request a special topic!

and inspiration hits. Contact me

to request a special topic!

|

The concept of immersion brings with it one strong command: sink or swim. In the music world, our immersions come in the form of workshops, symposia, and festivals, and we sink or swim just the same. As I return from another summer of musical immersion, I can't help but reflect on those I've seen swim beautifully... and those who struggled and sank. With such high stakes as your precious technical development, potentially wavering self-esteem, and sense of self as a musician and human, it's best to be sure you know how to swim. After a total of twelve summers and seven different types of musical immersion programs (many back-to-back in the same year), I think I have it figured out. Sinking is almost always a result of unreadiness in one of four ways. So when are you ready to swim? ... when you love something. If you don't love something, certainly don't surround yourself by nothing but highly concentrated versions of that and its biggest fans for a long period of time. Just don't do that to yourself. Is there something you love to the point of 24 hours not being enough? Is it music? If so, you're 25% ready for immersion. ... when you're confident. Immersion programs draw the best of the best, period. If you have gone through the type of audition or application process that most of these types of programs require, you have something to offer. Own it! Can you recognize your strengths and rock them? If so, you're halfway there. ... when you're ready to be wrong. But don't be too confident. These programs are designed to teach, and that requires a willingness to learn. Can you ask for and accept feedback and grow from it, without too many hurt feelings? If so, you're nearly ready. ... when you're ready for "camp friends."

Okay, I know festivals and workshops technically aren't "camps," but completely engrossing yourself in an experience completely engrosses you in the people. "Camp friends" are the ones you get to know the fastest and most intensely, the people who you tell secrets, even though you've only known them for two days. People can make or break an immersion experience. They can help you swim or drag you to the bottom, often with them. Congratulations! If you made it this far through the swimming checklist, you are ready for an immersion. You love something and know what you have to offer. You know that you are not perfect and want to improve. You are excited to find other people just like you. That being said, applications for most programs go live in about a month - now get out there and immerse yourself in something wonderful!

1 Comment

Okay, I get it. Slow down. In my experience, this is by far the most frequent practice advice given. In their exceedingly popular music blogs, Noa Kageyama asks "Is Slow Practice Really Necessary?", Gerald Klickstein explores "A Different Kind of Slow Practice", and Daniel Coyle shows us all how "Slow is Beautiful." Okay, I get it. For determined practicers, the problem is often not that we don't practice slowly. The problem is that we don't know how slowly. We show up to lessons insisting that we have been practicing slowly (usually we're not lying), and we hear week after week to practice slower. But slow is boring, and slow is confusing. How slow is slow enough? THE LONG(ER) ANSWER: I turned to the idea of mindfulness. Most basically, mindful practicing meant being aware of everything, all the time. When I did that, I practiced slowly and deliberately enough to see relaxed, lasting change. Without going too far into the psychology and meditation side of the movement, I found an ideal practice tempo by tapping into multiple senses. Specific questions helped:

Focusing on real-time sensations rather than long term goals slowed me down. I practiced less angrily. Repetitions felt like experiences, not like plateaus. The absolute best part about it, though, was that everything sounded like I wanted it to sound. I was like a kid in the nerdiest candy shop ever. Now for THE SHORT(EST) ANSWER: No: Practice so you can do everything right. Yes: Practice so you can do nothing wrong. Happy (slow enough) practicing!

Image borrowed from ADHD and Spring Cleaning: 10 Survival Tips, which also has an awesome list of steps to overcome distraction! About this time every year, all of humanity seems to go cuckoo for cleaning. Some even say it's ingrained into our cultural identity from our ancestors clearing out their dusty huts. Last year I went cuckoo and ended up re-caulking a bathtub. Cleaning can be therapeutic and invigorating. It's freeing, in a way, to have a literal fresh start. This year, I'm challenging myself to funnel my spring cleaning urges into musical things. (My bathtub caulk can temporarily fend for itself.) A couple of these are literal, physical cleanings. The others are figurative and psychological. Like that weird ribboned radio thing above, though, all are ugly and broken, and all need to be cleaned. Here are four highlights from my list, complete with plans of attack. Feel free to add yours below, and we can fight the good spring cleaning fight together!

So there you have it, a quick introduction to my musical spring cleaning list. Now that I've taken care of "going public," maybe I can actually bring myself to throw away that moldy recital reed...

Best of luck in your spring cleanings! Last week I sent a text message that used the word "just" three times. ... A text. I am especially guilty of using the word "just." I just want to tell people things. I just want to say... I'd just like to ask... I was just wondering... and it will just take a minute. For me, "just" doing something is often an apology. I'm sorry you're reading this right now - I just wanted to share something, and it will just take a moment of your time. As it turns out, when I started paying attention to this tendency, I found that it has seeped into my professional world, too. Two days ago, the awesome Christina Feigel and I taught a master class on giving constructive criticism that included scripted responses with students. As happens with scripts, ours became predictable and elicited some laughter and good-natured teasing. What was my response to that? "It's just one option of phrasing." WHAT WERE YOU DOING, PAST CAYLA?! That meant they were listening, and they learned. No apology needed. I even do it - and I bet you do, too - in musical and school situations:

Now, the point - I have decided to reclaim the word "just." "Just" is not always evil. Sometimes "just" keeps things in perspective. Sometimes "just" helps me focus. I put this plan into action last night, for the bassoon preliminaries of the concerto competition. I did a little powering up and made a positive "just" mantra. I am not going to do everything. I am not going to play with flawless technique. I am not going to be the poster child for authentic Baroque style. I am not even going to remember every note. And at the end of the evening, I hadn't played with flawless technique or glorious Baroque style. I hadn't even remembered all the notes. "Just" wasn't a perfect plan, by any means. But someone came up to me afterward to tell me how much he enjoyed it - "I mean, really." You know what I felt like? Yep, phenomenal cosmic power. "Just" wasn't a perfect plan, but it was a surprisingly empowering one.

I'm just going to leave you with that. "Hey, will you come listen to something?" At some point, we have all asked for feedback. Sometimes we ask explicitly, dragging people from the halls into our practice room to hear an excerpt, and sometimes it is the implicit request we make every time we show up for a lesson. This post is purely about that - asking for feedback. A couple of weeks ago, I read this article in the Chronicle for Higher Education. It is not about music, but many of the points resonated in my immediately-pre-audition mind. When we ask someone to critique our playing, what do we really want? In case you didn't actually read the article, I'll summarize - Allison points out that we need to be specific in what we want from our listeners. To translate her categories to music, we can ask for one of five types of feedback:

If you do indeed want feedback - you have asked for categories 1, 2, or 3 - the next step is interpreting what you receive. At this point in my thinking, I returned to the array of internet wisdom and found this post. The important part is what this suggests about interpreting feedback. Despite the catastrophic mentality of some of us, all critiques are not this: Similarly, if your critic says anything at all, it does not mean this: I venture to say that 99.a lot% of feedback lies somewhere between levels 1 and 9, and how we as players choose to respond to that feedback influences our future progress. To translate the author's example to music and add an extra interpretation of my own:

Feedback - "Your double-tonguing in Marriage of Figaro is too short." Interpretations -

Again, perhaps the most helpful interpretation of feedback lies somewhere between the extremes. As someone who tends toward the unclear feedback requests and catastrophic level 10 interpretations, I am making it my personal mission to shift my perspective. So here it is - if you see me practicing at any point this spring, come on in and listen. I'll be specific and do my best not to enrage the beast. As I hope your experiences support, the holidays are filled with parties, family dinners, and various musical opportunities, and with any group event comes a certain degree of collaboration. Sometimes these events can seem like chaos. Turkeys are brined, stuffing is stuffed, salads are tossed, rolls are baked... all too much for one person. In an ideal collaboration, each person has a job matched to his or her interests and abilities. In times of chaos, we lose this strategy in the tornado of food and drink, and it is far too easy to feel abandoned on the sidelines as your unused brining prowess atrophies. My point? Jump in and offer your skills. "Mom, sit down! I'll mash the potatoes!" Because my mashed potatoes are awesome. To extend the metaphor, I encourage you to find a way to mash the potatoes in your musical ventures over the next year.

Reflect on your own strengths and offer them proudly. Design posters, network, arrange music, coordinate schedules, lead rehearsals, program for your target audience, inspire invested performances, entertain. I'll mash the potatoes. "Technically, you played it correctly..." "Technically, everything was right..." "Technically, it was fine..." ... but? This post goes out to the several people over the past month who have asked me what to do when they've technically done it all. You know who you are, and you're not alone. I have previously referred to this performance trend as "playing apologetically." This can take many forms:

As impolite as it sounds, what if we didn't apologize? If no one wanted to hear you, they wouldn't be there. Even for "mandatory" school-related events, each and every audience member has chosen to listen to you perform instead of sitting on their respective couches ordering pizza and marathoning Netflix. What if we didn't apologize for that? What if, instead, we made it really and truly worth their while? We are all at least as interesting as another streamed episode of Law and Order or Gossip Girl. Sometimes I also think of this difficulty as "being camera shy." Shyness is about hiding, and in music this can be physically hiding behind our music stand or instrument. More often, though, it means emotionally hiding behind the ink on the page, rather than presenting what we actually believe about a piece and its message. For the sake of brevity, here I defer to these cute kids in this Dove commercial: When did you stop thinking you're worth hearing?

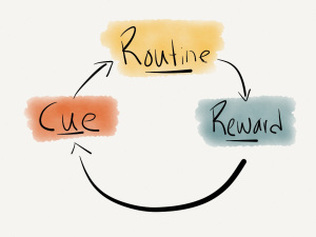

Throw away whatever hides you. Power up. Show off for the camera. Be unapologetic. "Practice doesn't make perfect. Practice makes permanent." Sound familiar? This idea of habit formation has been central to my most recent "Lap Four" goal - see my earlier post if you're confused. Historically, I have problems with consistency. One day I play a brilliant concerto, the next I forget how to slur an octave. Home run, strike out. In my multifaceted approach to solve this problem (and subsequent random internet surfing), I came across several videos, web resources, and a book by New York Times writer Charles Duhigg. He describes the "Habit Loop," which led me to two important realizations:

I set out to deconstruct my habit loop. CUE: Public performance. ROUTINE: Freak out, lose control. REWARD: An "engaging" performance. Sometimes this is a euphemism, sometimes not. Here's his story, the cookie-based version of my bassoon habit: After months of diligent work refocusing on the reward - engaging an audience with a musical experience - I finally stepped beyond my most recent plateau. I played in a master class, and, for the first time in what felt like forever, I was happy with what I presented.

I played representatively. I played how I play when I'm alone. I played how I play when I am having fun. *gasp* A friend of mine asked me later that evening what I felt to be the biggest change in my playing over the past several months, and I gave him a highly inadequate answer. (So, this post is partially for you, Adam!) I gave him a technical answer. I did blah blah to my reeds and think of my sound as blah blah and by body blah. Blah. After more reflection, here's the real answer: I practiced right. By "right" I don't mean that I was practicing wrong before. I mean I practiced being right and knowing I could be right. I practiced being right more than I was being wrong, which I had always before thought of as a waste of time. However, it stands to reason that we will always do what we have always done. If nine times out of ten you crack a note, that one success only means that you have a 10% chance the next time around. Play it correctly ten times in a row, then your chances just over 50% (11 rights for 9 wrongs). Math! I stopped practicing to be perfect, and I started practicing to be permanent. I practiced right, and it felt right. Go give it a shot, and let me know what you think! Warning: This post contains moments of tough love. Why do you practice? To move up in your section? To reach higher than your personal best? To increase your ability to connect with an audience? Up means improvement and success. Just take a look at my Google image search for "success": In practicing and learning, those "up" moments are brilliant. They encourage us, console us, validate us. Sure, the "down" moments sting, but it's the prolonged periods of parallel motion that are truly devastating. It hurts to work and feel no progress, it hurts when dedication doesn't seem to matter, and it hurts to watch others improve while you're stuck on cruise control. Plateaus are the worst. So now I offer you three "UP"s as options to take until you reach your next "up".

To conclude: I had a teacher once who equated the process of practicing and improving over the long-term to climbing a mountain - it is only at the end of your climb that you realize how high you've reached. In the meantime, though, remind yourself what you can do. Tell yourself you're awesome, because you are to someone (even if not yourself). Some plateaus can be just plain beautiful. "So, what do you do?" As musicians and students, we are oddly forgiving of inappropriate answers to this question, and as we meet hordes of potential friends at the start of each year, we reinforce the inappropriateness with conversations that go something like this: "Hi, I'm Cayla. I play the bassoon." "Oh, cool. I do, too." "What do you like to do for fun?" "I've never had much time for hobbies." *chirp, chirp* and icebreaker games that go something like this: "Tell us your name, what you study, where you're from, and something you like to do." "Hi, I'm Cayla, and I study music. I'm from Georgia. I play the bassoon." *wah wah* After these conversations and introductions, I find that I know next to nothing about the actual person next to me, and he or she knows nothing about me. More disturbingly, I used to find that the question of hobbies made me hesitate, too. The rare student who gets beyond that hesitation is not much more creative. What do you like to do in your spare time? More importantly, what do you do that makes you:

Sleep? WRONG. You need sleep to function. This is not a hobby. Eat? WRONG. See above. Drink? WRONG. This is, more often than not, code for "sleeping while I'm awake." Something relaxing but not engaging in the long run. This is not a hobby. Run? PROBABLY WRONG. Unless you run for the sheer enjoyment of running, you are using exercise for a secondary function of health or beautification. This is (often) not a hobby. Read? Knit? Play guitar? Hike? MAYBE. Why do you do it, really? One of the best things I could have done for myself over the past year was to channel my youthful hobbyist and join the fabulous Bloomingfoods co-ed softball team. I joined because I missed being what I had started calling a "real person" doing something with other "real people." When I was younger, this was not a rare experience. I played softball. I picked up trombone for jazz and marching bands. I wrote short stories (and even a novel once, literally my heaviest artistic contribution to the world). Here are a couple pictures of me looking cute and having a hobby. Other than reminiscing on our younger days, why do hobbies matter to us as musicians?

Music mandates that we be human. We have to roll in the dirt and know firsthand what it feels like to be cold, supported, like a failure, and so on. We have to live life to truly know pieces of it to share with other humans. Isn't that what we do? As we each enter a new academic year or performance season that pulls us in too many directions of too many commitments, I throw one more task in front of you. Find something that makes you YOU, independent of your studies, your work, your friends, and your background - something that makes you smile, that you would do if no one asked or noticed or praised, that makes you feel alive. And as an added bonus, you might be able to confidently answer the question I leave you with now: "So, what do you do?" |

Archives

October 2020

Categories

All

|